An unsettling and, at times, dazzling experience that lacks creative spontaneity and got the excess of TV cliches. Squid Game tries so hard to become a new episodic game-changer, but its deplorable social commentary quickly turns it into the grotesque modern morality play about good and evil. Therefore, if we treat the most popular Netflix series as non-invasive entertainment, then it’s gonna light our cinematic way for another eight hours and five minutes.

A few years ago, we got Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games, a pretty enjoyable read (and adaption, too) depicting an Orwellic anti-utopian society where people are chosen to fight to the death. Remember that one? If so, then Squid Game won’t be a surprise, that’s for sure. The concept works similarly, however, this Korean show draws scenario layers from different, much more psychological sources. The eponymous game is not the one where people MUST participate. It is rather an opportunity in which they WANT to be. The price? Oh, yes, you know it. Give it a shot. Are you thinking of money? You’re thinking right.

We meet this main hero, a forty-something guy called Seong Gi-hun, a nonsensical bum who has no job and a huge debt, he is a pretty bad father and the cherry on top? He financially cheats on his old mother. His behaviour is most arrogant, and I can’t find even one argument that might help us like him. Because of the lack of money, he participates in the Squid Game competition, just like the other heroes. And here, as you could already figure out, Seong will take a path of metamorphosis. On paper, it looks attractively, although Gi-hun’s personality is changed with a snap of the finger. There is no development, and one can feel like Seong Gi-hun just wakes up already changed — after a good night of sleep during the first episodes.

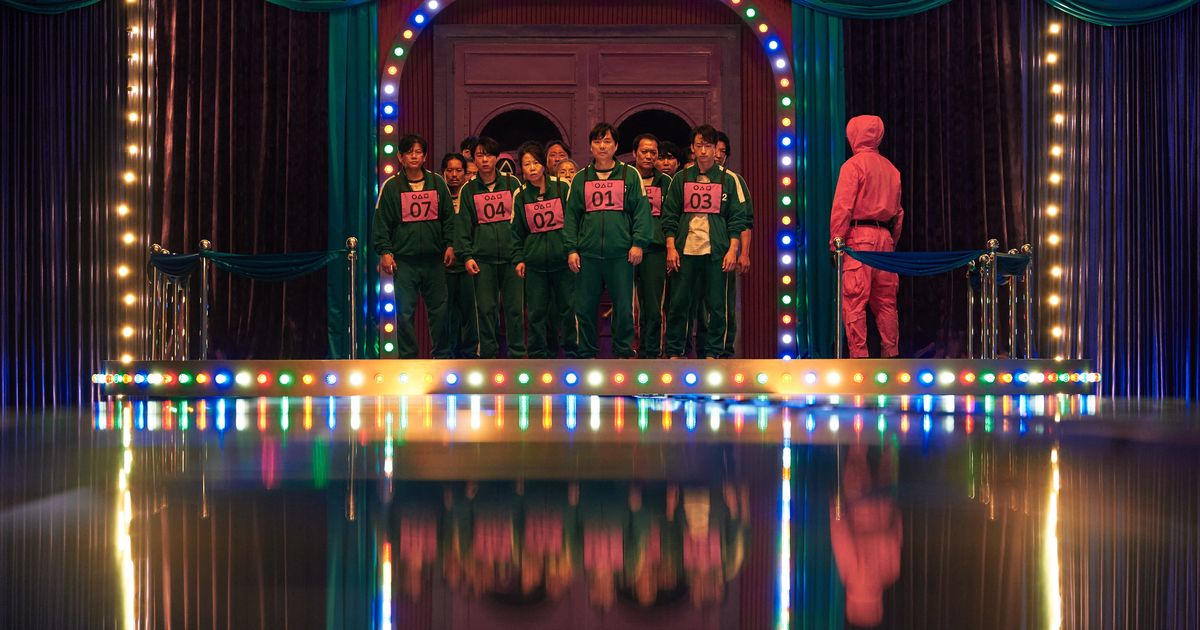

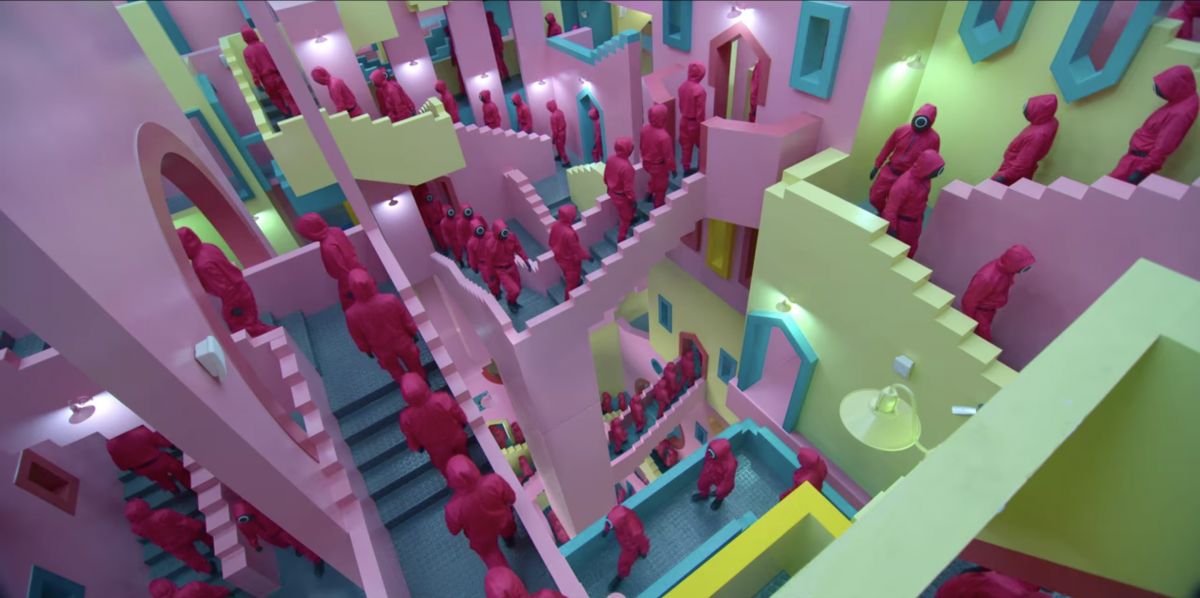

Squid Game’s aesthetics are illusory, just like the rules of the whole game. The series fills the frames with calm colours that, theoretically, should soothe the emotions of both contestants and us, the viewers. We are forced to believe that the whole competition will be pure fun and, as you already assume, it is not. Have you ever heard about the stylish death? Well, Tarantino tried to create a few ones, and so are trying the Squid Game screenwriters.

The rules of the games draw from traditional Korean jollities. The idea is skilfully shifted into the modern world of Squid Game, so every game is a mystery the audience would like to see as soon as possible. Consequently, people are dying in this colourful, no-stress environment. Participants are wearing blue colour and organisers are fancying the red one. Everything is so purified that we forget about the game’s rules. As the audience, we fancy colours, the impetus of the production or the Korean background, which is so unfamiliar for the British viewers. But it is ephemeral. And if we forget about the importance of death (in the series about death), then what other factor is supposed to keep us interested?

Of course, my judgment should be more favourable as I called this series “dazzling”. And yes, there are times when Squid Game meets us with this inevitable grasp of binge-watching. As the viewers, we start treating these archetypical characters like our beloved favourites. Like, seriously, we count on them and hope that they’ll make it to the end. Their screen time is flawlessly calculated; everyone has enough time to meet them, understand their nature, and “choose our fighter”. Besides, the tempo of the production supports the relationship dynamics. Intervals between the games are often well-calculated: thanks to that, the series smartly manoeuvres between calm and stress-inducing moments.

Also, maybe I’m just drawing the wrong conclusions (if so, please crucify me), yet, I believe that the series is insistently trying to imitate the genre composition of another Korean hit, Parasite. In Squid Game, we can find family drama, thriller, comedy, horrour, or even some social commentary. The last one, with its wry anticapitalistic undertone, is just too easily made. Well, we can call it an emblematic moral. Rich people are compared to the so-called demons, and this analogy makes a resemblance to our world. A world where it is believed that corporations like Amazon deprive poor people of their dignity. If you decide to make such a statement, then at least make it more subtle (like in the Parasite mentioned above). In the end, comparing the wealthiest companies to the fascists killing for fun seems to be more grotesque than telling.

While it won’t endure in the cinephiles’ future memory, Squid Game will eventually become the newest Game of Thrones with three or four other seasons (as the concept can be extended to infinity). Nevertheless, are we ready to watch another brutal, naturalistic competition where death fills our laptop screens? As we see how insensitive we have become in the XXI century, I guess we all can treat Squid Game as a joy to watch during family dinner. Otherwise, there’s no sense in watching it as another season of Succession has just arrived.

Article Written by Features Writer – Jan Tracz